Ralph W. Hammett

When Ralph W. Hammett (1896-1984) came to Ann Arbor in 1931, he brought with him excellent credentials. He had acquired an architecture degree from the University of Minnesota in 1919 and an M.A. from Harvard in 1923. Two years of travel, afforded by winning the Rome Prize at Harvard, led to a sumptuous book of photographs titled Romanesque Architecture of Western Europe: Italy, France, Spain, Germany and England: Illustrated and with a Brief Historical and Descriptive Text by Ralph Warren Hammett (1927). While teaching at the Armour Institute of Technology (now Illinois Institute of Technology) in Chicago (1927-1931) he worked at the Chicago firm of Hall, Lawrence & Ratcliffe, Inc., as a renderer, designer and planner. He joined in several substantial projects—a 35-story office tower, an apartment building, a nurses’ home and hospital, a courthouse, and an indoor stadium—for this firm. In 1930 he was the architectural editor of Architectural Annual Chicago 1930, a record of outstanding construction projects in Chicago at that time that included pictures of several Hall, Lawrence & Ratcliffe buildings.

When Ralph W. Hammett (1896-1984) came to Ann Arbor in 1931, he brought with him excellent credentials. He had acquired an architecture degree from the University of Minnesota in 1919 and an M.A. from Harvard in 1923. Two years of travel, afforded by winning the Rome Prize at Harvard, led to a sumptuous book of photographs titled Romanesque Architecture of Western Europe: Italy, France, Spain, Germany and England: Illustrated and with a Brief Historical and Descriptive Text by Ralph Warren Hammett (1927). While teaching at the Armour Institute of Technology (now Illinois Institute of Technology) in Chicago (1927-1931) he worked at the Chicago firm of Hall, Lawrence & Ratcliffe, Inc., as a renderer, designer and planner. He joined in several substantial projects—a 35-story office tower, an apartment building, a nurses’ home and hospital, a courthouse, and an indoor stadium—for this firm. In 1930 he was the architectural editor of Architectural Annual Chicago 1930, a record of outstanding construction projects in Chicago at that time that included pictures of several Hall, Lawrence & Ratcliffe buildings.

Guided by Emil Lorch since 1906, the department at Michigan had a modernist-leaning program. In the 1920’s, architects Louis Sullivan and Eliel Saarinen were brought to the campus (Eliel Saarinen to teach architectural design for two years—1923-1925). Very much in this current, Ralph Hammett had published an essay in the Minnesota-based periodical Western Architect in 1929, titled, “The Machine Age in Architecture.” His topic elaborated on the overly familiar trope of “form follows function,” a phrasing Louis Sullivan had made famous before the turn of the century. For Ralph Hammett, the machine age brought with it an added responsibility for the modern architect. He pointed to the automobile as an example of a completely designed and aesthetically successful machine-age product, a modern demonstration of form and function in balance. Architects could learn from this. Certainly, a factory building must realize its simple role of housing machines in workspaces in the most efficient and economical way, but the building itself did not have to be ugly. Realizing economy and machine-like efficiency were not the only ends for an architect, at least not for the modern architect. Architecture must recognize the fact that “the philosophy of the machine age is a bit different from any age which has preceded.”

If our buildings are to be true aesthetic expressions of function as well as expressions

of the age in which they are built, designers must be more profound in their study of

each particular problem. Beginning with the practical requirements of the problem,

they must rise to the creative expression of great artists. They must recognize certain

inevitable limitations of function, materials and structure. In fact, they must make

actual creative possibilities out of these limitations. Theirs must be the art of practical

men, scientists who are able to make their work fine art. (Western Architect, May 1929,

p. 73.)

Arriving in Ann Arbor in the midst of a worsening Depression, Ralph Hammett found ways to teach and entertain his students in spite of limited resources. He used local architectural examples in teaching architectural history, and he had students to his house at 1425 Pontiac Road. In 1933 he had purchased the famous but at that time grievously run-down Guy Beckley house (it had been one of the stopping places on the Underground Railroad), over time updating and restoring it with great sensitivity.

He was civic-minded, as well. In the mid-30’s he was President of the North Side Civic Association. He became Alderman for the 5th Ward in 1936, serving on the City Council from 1936 to 1940. In this role he helped in organizing the City Planning Commission in 1938, and he participated on the panel that devised the Ann Arbor Building Code. Through his steady advocacy, the West Side Park Band Shell came into being in 1938.

In these years his wife, Gladys, was a prominent figure in the Ann Arbor Garden Club, which contributed its support to the Band Shell project and encouraged the Attractive Ann Arbor competition in 1937. Joining with the Ann Arbor News, the Garden Club anticipated the Centennial celebration at the university (1837-1937) that would attract thousands of alumni/ae back to the campus and to the city. The Ann Arbor News continued the Attractive Ann Arbor competition in 1938. Large and small residences were honored for their appearance and landscaping as a way to spur citizens to beautify their homes. In both years the Hammett house was on the list of awardees. In June 1938 the Convention of Federated Garden Clubs was held in the Earhart mansion, The Meadows, with university involvement.

Exhibitions of rare books brought the gardeners to the new Rackham Building and the Clements Library, and they were invited to visit the University Library, the Michigan League and the Michigan Union. Mrs. Hammett chaired the committee that planned the 300-seat luncheon in the Union as well as the evening banquet. In 1942 Gladys Hammett was named president of the Ann Arbor Garden Club.

In the Second War, Ralph Hammett came off the bench, so to speak, having served in the Navy in WWI. He entered the US Army’s Civil Affairs Training School at 47, enlisting in late August and receiving the rank of Captain. He was assigned to the European Civil Affairs Division. At first, these men assisted in combat operations. For example, Ralph Hammett was credited with protecting Chartres Cathedral from bombardment by American soldiers when German snipers were holed up inside. He became famous, however, for devising the card catalogue for the Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives Section, which was tasked with recording and cataloguing art objects and cultural artifacts, stolen or otherwise, gathered by the Army as the Germans retreated across France. For his service to France, Ralph Hammett was awarded the Palmes Academiques, Officier d’Academic de France in 1945. The recent book about the Monuments Men by Robert Edsel, The Greatest Treasure Hunt in History: The Story of the Monuments Men, became the popular film The Monuments Men in 2014. Ralph Hammett though not impersonated in the film per se was one of the men who inspired the story.

The work of the Monuments Men continued until 1951, but he returned home in mid-1945. The university had extended his leave only to that time. While he was away, Mrs. Hammett had become the director of the rental office at Willow Village in Ypsilanti, which in 1946 was filling up fast with students seeking housing near the university. In 1947 Ralph Hammett and Frederick C. O’Dell took on the commission to design a parish hall and chapel for St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church. This project used fieldstone for the exterior face of the new addition, evoking a modernist-Romanesque aura as a result. But his interest was also focused on the small house. In 1948 he wrote a series of short advice pieces for publication in the Chicago Tribune on the topics of building/buying a small house, the purchase of a lot, and issues of upgrading the property. His lectures for the summer school class he taught in 1948 – 1949 covered his research on the small house as well as more traditional topics. At this time, he had also become involved in the Michigan Society of Architects (MSA), acting first as a director in 1947 and then moving to 3rd Vice President in 1948, 2nd VP in 1949, and 1st VP in 1950. In 1949 he spoke to the American Association of University Women at Wayne on the subject of national housing issues. He called for a survey of housing in the present day, because he disputed the popularly repeated claim that 1/3 of Americans were ill housed. In his view, housing was a local issue not a government issue, and he encouraged his audience to advocate for planning at the local level rather than wait for government direction.

The MSA leadership made him chairman of several committees, as he was an effective leader who moved forward with well-made plans. Committees included chairman of the education and research committee, state architectural board exams committee, state building code committee, and the small home design competition committee. He also took on planning the MSA State Convention in March 1952 and the Summer Conference at the Grand Hotel on Mackinac island. In 1952, Lynn C. Smith, UM ‘42a, became President of MSA, at 35 the youngest man to hold the post. He appointed Ralph Hammett secretary to the executive committee. Further committee work came under his authority, usually for planning complex events, like the centennial celebration of the AIA in 1957, or a visit by the Society of Architectural Historians to Detroit in 1957.

Of interest is the MSA Small Home Competition held from November 1951 to February 1952. This competition was open to the 500 architects in the state who were challenged to design a house to these specifications: 1,400 sq/ft, 3 bedrooms, pitched (not flat) roof, 2-car garage but garage door not facing the street, to be designed for an owner with an income of $8 – $12,000, and to be located in a suburban (meaning landscaped) setting. At just this time—1951-1952, so it seems—here is the formula for the Ann Arbor version of the Mid-Century Modern house. The germ of the idea seems to be here, but over time the modest plan then scaled up and outgrew the original conception.

In the 1950’s and ‘60’s Ralph Hammett designed a number of fine buildings while continuing to teach his classes. He retired in 1966 at the age of 70, becoming professor-emeritus, a long-beloved figure among faculty, students and alumni. The Regents’ citation said of him:

Professor Hammett revealed a nicely balanced feeling for the changing aspects of architectural practice and for the permanent. He taught and wrote on the history of architecture and concerned himself with the preservation of past architectural

monuments, while retaining a lively interest in the modern scene and sharing with his students his practical contemporary expertness. (Regents Proceedings 33)

These words encompassed well his readiness to embrace the new without rejecting the old. This stance tended to go against the orthodoxy of the Modern movement in the US that culminated both in the dismissing of non-Modern architects and in the mixed success of urban renewal projects in the 60’s and 70’s.

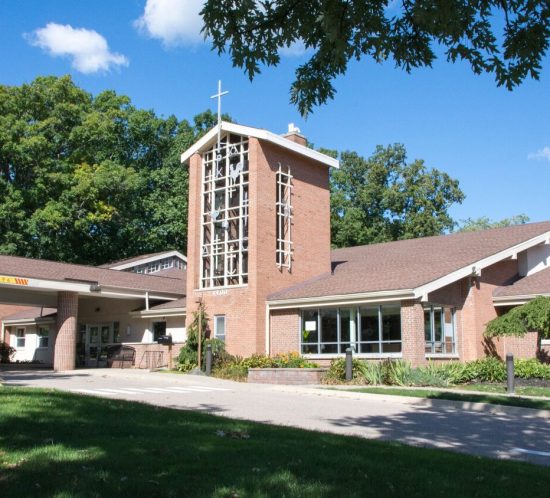

By 1950 Ralph and Gladys Hammett were eminent figures in Ann Arbor. In 1951, Gladys Hammett became the first president of the Ann Arbor Women’s City Club. As the club grew, Ralph Hammett provided the handsome addition in 1962 that included a dining room, auditorium, office, lobby and member lounge. As a result of a series of fine buildings that included the Lutheran Student Association Chapel at Hill and Forest Streets in a contemporary style (1951), the Douglas Memorial Chapel and Parish House (1952), the Peoples’ Presbyterian Church in Milan, MI, an Allergy Clinic for Dr. L. Dell Henry—one of the largest and most elaborate privately owned medical buildings in Ann Arbor (1955)—and his own Mid-Century Modern house on Riverview (1957), he was named Architect of the Year by the Michigan Society of Architects in 1957. Mrs. Hammett was also included in the citation, for her involvement with historic preservation. In 1963 the Detroit Chapter of the American Institute of Architects awarded him a Gold Medal for his outstanding service as a teacher, historian and practicing architect.

A year after retirement, Ralph Hammett joined the Ann Arbor Historic District Commission. Just in time, it seems, to take on the restoration of the Reuben Kempf House at 312 Division Street. A classic example of Greek Revival architecture, this building came under the control of the city in 1969. In October the Ann Arbor City Council passed a resolution of commendation for Ralph Hammett who had spent untold uncompensated hours on this project. In this year also he received an honorary degree from Carthage College in Kenosha, WI, for his work on the Trinity Evangelical Lutheran Church and for the People’s Presbyterian Church in Milan. He moved to Rochester, MN, in 1977 and passed away in 1984 at the age of 88.

Ralph Hammett traveled extensively in the years 1924-1926 (studying Romanesque architecture), 1943-1945 (rescuing and resorting European culture), and 1953-1954 (Portugal, Spain, France, Switzerland, Italy, Germany and Holland, as well as delivering 6 lectures at the American Academy in Rome on Ancient Roman Construction in December of 1953). Writing from Japan in 1965, his observations on the Japanese use of technology showed the rapid evolution of that culture since wartime. Ann Arbor News (18 November 1965) readers learned that quiet, vibration-free elevated superhighways brought three million additional people daily to work into Tokyo (a city with a population already at ten million people); that express trains traveled between cities at speeds of 125 mph, and that the subway system in Tokyo was as extensive as that in New York City.

His travels also fed directly into his teaching and publications. His study guides for students of architectural history demonstrated first-hand experience with many of the buildings featured in them. His much later survey of American architectural styles published in 1976 identified buildings with one or two stars to indicate those of particular note. His comments indicate that he had seen many of them at first-hand. His remarks about buildings in the chapter on “The Jet Age” reveal a special sensitivity to changes occurring in contemporary times. For example, he gently chided the architects of the Ford Motor Company’s “Glass House” in Dearborn regarding its orientation:

it is an example of a glass-cage building that has its principal elevation facing south on hot summer days even air conditioning and glareproof green glass can hardly compete with the heat of the sun. In the summer offices on this side of the building have to be vacated from midafternoon onward, especially during the golfing season.

He also noted the negative impact that later buildings built on a difference scale can have on those already in place, an example being Eero Saarinen’s TWA Terminal: “This building is interesting and beautiful; however it has become crowded between other and larger airline terminals. Instead of a bird in flight it now has more of the appearance of a sitting duck. It lacks scale in its environment, a shame because it should be set off by itself.” His balanced feeling for architectural practice old and new remained intact throughout a long and distinguished career, and his would be a discerning and valuable voice today as the city and the university move ahead with sometimes overly massive building projects whose scale threatens the fragile monumentality and the familiar identities of existing structures that can too easily become sitting ducks.

Other of his projects include:

While in the employ of Hall, Lawrence and Ratcliffe, Inc., of Chicago:

Cook County Criminal Court Building, 1927

Chicago Indoor Stadium, 1929

Raymond Park Apartments, Evanston, IL, 1930

Abraham Lincoln Memorial in Springfield, Illinois, 1931

Nurses’ Home, part of Cook County Hospital, 1932

Projects in Michigan:

Addition to Bethlehem German Evangelical Church, 423 South Fourth, AA, featuring a school gymnasium and a small auditorium, 1932-1933

Guy Beckley House, 1425 Pontiac Trail, AA, purchased in 1933 and sensitively restored

Remodeling Wurster Dairy Co. exterior of building at 1015 Broadway Street, AA, 1936

Alteration of Dr. Kellogg’s Medical Works building at 1001 Broadway Street, AA, 1937

Ruth Wanstrom/Margaret Leary House, 1056 Newport Road, AA, residential project, 1942

Bethlehem Lutheran Church, 549 East Mount Hope Avenue, Lansing, MI

Uolevi Lahti Residence, 909 Sunset Ridge, AA, 1948

Arthur Allen Residence, Midland, Texas

St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church Parish Hall, 306 North Division Street, AA, designed with

Frederick O’Dell, 1951

Lutheran Student Associated Chapel, at Forest and Hill Streets, AA, 1951

Lloyd C. Douglas Memorial Chapel and Parish House for the First Congregational Church at 608 East William, AA, 1952 (The Douglas bequest specified Gothic architecture)

Peoples’ Presbyterian Church, 210 Smith Street, Milan, MI, 1953

L. Dell Henry Allergy Clinic, 706 West Huron Street, AA, 1955

485 Riverview, his Mid-Century Modern home, AA, 1956 https://aadl.org/aa_news_19570227-home_with_two_exterior%20faces_occupies_hilltop_site

New Wing added to Pi Beta Phi Sorority House, 836 Tappan Street, AA, 1958

New Trinity Lutheran Church, 1400 West Stadium Boulevard, AA, 1959

Restoration of Ruben Kempf House at 312 Division Street, AA, 1970

Addition to Ann Arbor Women’s City Club, 1830 Washtenaw, AA, 1962

https://aadl.org/taxonomy/term/52117

Bibliography:

The Romanesque Architecture of Western Europe: Italy, France, Spain, Germany and England. Illustrated and with a Brief Historical and Descriptive Text. New York: The Architectural Book Publishing Company, 1927

Architectural Annual Chicago 1930. Chicago. Architectural Annual Company, 1930.

“Comzone and the Protection of Monuments in Northeast Europe.” College Art Journal 5, 2 (January 1946), 123-126.

Study Guide: History of Architecture, Ancient to Medieval. Ann Arbor: The Edwards Letter Shop, 1946, 1948.

Architecture in the United States: A Survey of Architectural Styles Since 1776. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1976.

Websites:

Ralph W. Hammett, Monuments Man

Professor-Emeritus of Architecture Dies

Ralph Warner Hammett

See also: “Ralph W. Hammett,” in Monthly Bulletin, Michigan Society of Architects 30, 11 (November 1956), 17-30.

By Jeffrey E. Welch

All Rights Reserved

May 2020

Research Article:

The Three Lives of 1830 Washtenaw