On Sunday afternoon, May 3rd, there will be three tours of the Oslund condominiums here in Ann Arbor.

The cost of the tour is $15 per person. To register click here: http://www.a2modern.myevent.com/

Oslund was David Osler’s most personal work a�fter his house and office. Located on what had been

his family’s farm, he cared deeply about the site and was in total control of the design. The resulting

project, 27 condominiums built in three phases between 1987–2005, was designed for clustered

density, yet each unit is totally private. “He did Oslund for himself, it was a whole different concept,”

recalls Connie Osler, David Osler’s widow.

Osler (1921–2014) moved with his family to the farm when he was four years old. When the

Depression hit they were able to survive by supplementing his father’s income as county agricultural

agent with the farm produce. Scott Van Sweringen, the architect who was project manager on the

first phase, remembers that by the time they began the project “the land was mainly scrub grown

over, but we looked to see if there were trees to save.” They did find some birches that were

incorporated into internal gardens and still are there. They also saved pine trees that Osler and his

brother Scott had planted.

The units in the first phase are entered through the first of the three gardens, into a low entrance,

leading past a galley kitchen, into a cozy dining room that looks out onto the second garden, and

then up three steps to an elegant high-ceiling living room surrounded with a garden on two sides.

Helen Aminoff, long time Osler business manager and a resident in one of the first phase condos,

describes the units as “opening up like a flower,” to which Molly Osler, Osler’s daughter, adds, “you

experience it as a series of events.”

Minor changes were made in the second phase units including moving the location of the stairs to

the basement thus creating a larger kitchen and removing the steps to the living room, a request

from people interested in aging in place.

The condos were carefully designed to fit the site. The steep-roofed garages, which front the units,

are in a stepped-up pattern following the rise of the land. “It’s more interesting than if they were just

lined up,” says Van Sweringen. The basements were dug and then the ground filled back in for the

gardens. Because of the various stages of the projects, Van Sweringen recalls that they had to call a

surveyor in several times, and adds “the visual interest came with a price.”

Privacy also was carefully thought out. “You can’t see into windows, they are visually restricted, it

took great effort to do this,” explains John Miller, builder on the last two phases. “The gardens

extend the living space,” explains Jim Scrivens, the architect who was project manager for the

second and third phases. “With the high density, they needed outside space to look out at, plus

it created natural light.” The three gardens are enclosed by high brick walls, making window

blinds unnecessary.

The design of the gardens was le�ft to the residents and varied from rose gardens to vegetable ones

and everything in between. Some people put in decks. One requested a sunken pool. The plants for

the exterior landscape, Amur maples and ground cover and shrubs, were selected by landscape

architect Chuck Cares. The two roads were named Scott, a�fter Osler’s brother, and Young, his

mother’s maiden name.

The “os” in the name is of course from Osler (pronounced with a long o), while “lund” is the Swedish

word for wooded glen. The Scandinavian influence is most noticeable in the painted white brick and

the internal gardens. “They had beautiful little towns,” recalled Osler in a 2012 interview. “The

buildings were simple, straight forward. I learned a tremendous amount.” In the same interview he

said of Oslund that he particularly liked the “angles and gables, creating sharp shadows,” adding, “I

love it when it’s crisp.”

The units in the first phase were the hardest to sell. “Those who could afford them were used to

more conventional houses and had trouble seeing themselves in that environment,” recalls Van

Sweringen, “while younger people liked it but they didn’t have the money.” The worsening economy

added to the troubles, as did problems with visualizing the final product which potential buyers had

to imagine from models and house plans. Complaints included the lack of a picture window in front,

the size of the galley kitchen, and the lack of a long view. But those with imagination could order

finishes they wanted. One wanted stone floors throughout, others wanted different fireplaces. The

space above the garage was left� unfinished so each occupant could decide its use such as office,

exercise room, art studio, or guest bedroom.

In the second phase, because they were pre-sold but could see the finished products in the earlier

phase, a number of changes were made on request such as moving walls to give a more open

feel, changing the kitchen layout, and basement finishes. Because of the city’s desire for a smaller

footprint and the lay of the land, Osler was able to design the phase three units as two stories, some

with an exposed basement, allowing more daylight into that area.

Today the units sell almost as soon as they hit the market, oft�en at prices higher than the listing.

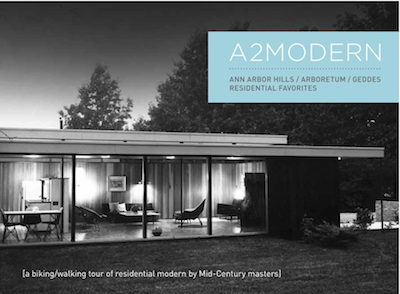

Photo: Courtesy of Bentley Historical Library.

Modern Cuba: Slideshow by Howard Shapiro in his 1965 Alden Dow house, 7 Regent Drive

Modern Cuba: Slideshow by Howard Shapiro in his 1965 Alden Dow house, 7 Regent Drive