At UMMA – The Michigan Union and the Michigan League – through May 7th

Author: Jeffrey Welch

Here at the Bentley Wall in UMMA, one may pass an agreeable hour perusing photographs, drawings and collectibles related to two of the finest and most familiar buildings on the Michigan campus. Find Level 3 in the new wing of the museum to view the show “Constructing Gender: The Origins of Michigan’s Union and League.”

The Bentley Library in conjunction with the museum has brought together a visual narrative highlighting the Michigan Union and the Michigan League buildings in the context of their functioning as sanctuaries for men and women, who at the time were far away from home and campus bound. Nancy Bartlett, Associate Director at the Bentley and responsible for this exhibition, one of the Bentley’s contributions to UM’s bicentennial celebration, introduced the show on Sunday, February 19th.

Michigan League

In her presentation (which one hopes will become a collectible pamphlet/catalogue) Nancy Bartlett explained that both buildings originated from the same architecture office, Pond and Pond. And they conformed to gender roles largely defined by the Pond brothers. In a nutshell, the Union shielded males from female scrutiny. It provided a democratic gathering space open to all the university men and not just to club men. In contrast, the League provided gathering spaces where activities could incorporate a desired male participation. The Union was given wide halls, colorful decoration, a billiard room and a swimming pool (open to women from the beginning but with restrictions). At the League, many generous-sized rooms for female and male gatherings opened on the narrower corridors, though some rooms, like the large Hussey room, were for women only. Also, a theater for university productions, given in memory of Lydia Mendelssohn, enriched its cultural attraction.

Michigan Union

The Pond brothers earned their degrees in the late 1870’s at UM under supervision by architect William Le Baron Jenney, and they located in Chicago at the time W. L. B. Jenney was inventing the steel skeleton for the skyscraper. At Michigan, the men had no place on campus to gather or socially to meet with professors or to share a meal. Hence, the drive to build a Union building with a dining room. With their numbers ever increasing, the university women and alumnae wanted (and quickly acquired) a League of their own. By 1922, when the League was in planning, the campus had been given zones along the State Street axis for buildings, with athletics and literary buildings on the south and west and science and women’s buildings on the north and east.

On the Bentley Wall, photographs of the Pond brothers, the long-lived Union doorman, and interiors with students disporting themselves are mixed with elevation drawings, an exquisite drawing of a custom-designed billiard table, and collectible objects in display cases. On one side, dance cards show how seriously students prepared for and pursued the many social activities located in these buildings. The other case displays postcards that served to spread the images of the Union and League buildings, creating icons for “The University of Michigan” that became familiar to people all over the world.

This show is one in a continuing series on architecture, devised by the Bentley Library to enrich understanding of university and Ann Arbor history within the context of developing ideas of modern architectural practice. The Pond Brothers were modernists in their time, and this show gives a delightful glimpse into the nexus of architecture and social life at the university. It is a charming show, one not to be missed.

The Detroit Area Art Deco Society invites you to the International Coalition of Art Deco Societies’ World Congress on Art Deco – and the Pre-Congress stop in Detroit from May 10 through May 13!

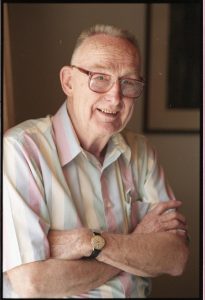

The Detroit Area Art Deco Society invites you to the International Coalition of Art Deco Societies’ World Congress on Art Deco – and the Pre-Congress stop in Detroit from May 10 through May 13! We were deeply saddened to learn that Robert C. Metcalf passed away on January 3, 2017 at the age of 93.

We were deeply saddened to learn that Robert C. Metcalf passed away on January 3, 2017 at the age of 93.

We are deeply saddened to post that Nancy Deromedi, one of the founders of a2Modern, passed away at home on Oct 13 at age 52 after saying her good-byes to her loving family and close friends. She had bravely waged a year-long fight with esophageal cancer. She made her mark on those who worked with her and who shared her passion for Ann Arbor’s rich legacy of mid-century modernism architecture, and she will be deeply missed.

We are deeply saddened to post that Nancy Deromedi, one of the founders of a2Modern, passed away at home on Oct 13 at age 52 after saying her good-byes to her loving family and close friends. She had bravely waged a year-long fight with esophageal cancer. She made her mark on those who worked with her and who shared her passion for Ann Arbor’s rich legacy of mid-century modernism architecture, and she will be deeply missed. Her innovative ideas for solving some of the profession’s most complicated challenges were awarded support by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the National Historic Records and Publications Commission, and the University of Michigan Information and Technology Services. Her work inspired a new publication series of the Society of American Archivists, entitled Campus Case Studies, and her reputation led to invitations to present at professional conferences as far away as Beijing, Copenhagen, Paris, Vienna, and throughout the U.S. She was also a regular guest lecturer with the School of Information, the Society of American Archivists, Midwest Archives Conference, and others.

Her innovative ideas for solving some of the profession’s most complicated challenges were awarded support by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the National Historic Records and Publications Commission, and the University of Michigan Information and Technology Services. Her work inspired a new publication series of the Society of American Archivists, entitled Campus Case Studies, and her reputation led to invitations to present at professional conferences as far away as Beijing, Copenhagen, Paris, Vienna, and throughout the U.S. She was also a regular guest lecturer with the School of Information, the Society of American Archivists, Midwest Archives Conference, and others.