Originally published in: Ann Arbor Observer, August 1998

Inspired by a teenage trip to Japan, the Dow Chemical heir spurned the family business to devote his life to architecture. From city hall to the U-M’s administration building, he put a quirky modernist stamp on the city.

Judy Dow Rumelhart was walking down Fifth Avenue one day recently when it started to rain. Looking around for shelter, she spotted the Ann Arbor District Library, a building originally designed by her uncle, Alden Dow. “And I thought how lovely it is,” Rumelhart says. “The library is one of my favorites.”

“The library and city hall are two of the ugliest buildings in Ann Arbor, and ISR [the U-M Institute for Social Research] is right up there,” says library board member Ed Surovell, expressing a dissenting opinion on the library and two other Dow designs. “They do not have the kind of imposing presence of a public building that creates civic pride.”

Alden Dow (1904–1983) is an unlikely figure to provoke such controversy. Though Frank Lloyd Wright once called him his “spiritual son,” Dow had none of the older architect’s egotism or self-promotion. Shy and studious, Dow had to be encouraged to take on major public commissions by his devoted wife, Vada. He got much of his work through family connections; his father, Herbert, was the founder of Dow Chemical.

Alden Dow’s entree to Ann Arbor was through his sister Margaret and her husband, U-M physician Harry Towsley. His first residential commission, in 1932, was the Towsley home in Ann Arbor Hills. Over the next thirty-six years, Dow designed seventeen more Ann Arbor buildings; in the 1960s, his work was so highly regarded that both the city of Ann Arbor and the U-M hired him to design their administrative centers: the Larcom Municipal Building (1961) and the Fleming Administration Building (1964).

Like Frank Lloyd Wright, with whom he studied, Dow sought to integrate his buildings into their environment. His motto was, “Gardens never begin, and houses never end.” Especially in his residential projects, he was capable of blending building and landscape brilliantly.

The going was tougher when the commission was a civic building downtown. He sometimes attempted to domesticate these urban settings by specifying massive upper-story planters, but in Ann Arbor, most of these have long since been abandoned as impractical.

Despite the common elements he sometimes used, Dow was no assembly-line architect. His Ann Arbor buildings have evoked comparisons as diverse as “a Mondrian painting” (the Fleming Building) and a “bureau of drawers” (city hall). But especially in recent years, those characterizations have not always been flattering.

Last year, shortly after taking office, U-M president Lee Bollinger announced that he wanted to move his office out of the Fleming Building, which he called “fortresslike.” (Its slit windows, arched entryway, and looming overhangs do give the Fleming Building a defensive look, but the popular belief that Dow designed it to shut out student protesters is unfounded—the plans were completed well before the campus demonstrations of the 1960s turned violent.)

Others have since risen to the building’s defense, including Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown, the celebrated “postmodern” architects whom Bollinger retained to develop a new master plan for the university. But Bollinger’s comments are a sure sign of Dow’s declining stature in the city he did so much to shape.

Alden Dow was born in Midland in 1904, the fifth of Grace and Herbert Dow’s seven children. His parents had assumed that he would go into the family business, but they also encouraged his creativity by exposing him to art, historic buildings, and gardens. When he was a teenager, the whole family took a trip to Japan. “They went in a big ship and stayed for three or four months,” relates his niece Judy Dow Rumelhart. The trip exposed Dow to two of his greatest influences as an architect: the exacting simplicity of Japanese design and the striking modernism of Frank Lloyd Wright, whose newly completed Imperial Hotel the family admired.

Dow spent three years at the U-M studying mechanical engineering, but then begged his parents to let him switch careers. He transferred to Columbia’s School of Architecture and in 1930, while still a student, his father got him his first commission: a clubhouse for the Midland Country Club. Upon graduation, Dow joined a Saginaw firm and married Vada Bennet, his childhood sweetheart, in 1931. His sister and brother-in-law, Margaret and Harry Towsley, promptly hired him to design their home.

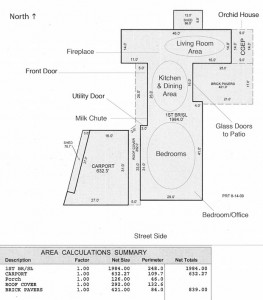

As originally designed, the Towsley house was basically a three-bedroom ranch, although much more elegant than those that would become ubiquitous after World War II. Its features included clerestory windows, a copper roof, and raised planter boxes designed to blend house and landscape.

Dow designed the interior of his houses in minute detail and even dictated the color schemes. “He loved strong colors, primary colors, and jewel tones,” recalls Rumelhart—“cherry red, cerise, emerald green, purple amethyst, ruby topaz.”

Considering Dow’s great interest in gardens, it’s ironic that his most influential innovation at the Towsley house was the way he designed the driveway: he specified an attached garage facing the street, believed to be the first in the country. “We thought the house looked like a gas station,” recalls family friend Jack Dobson.

Asked whether it was strange to grow up in such an unusual house, Rumelhart replies, “I loved the house. . . . and had a sense of pride of being in it. I thought all architecture should look like that.”

During construction, Dow fought repeatedly with city building inspectors, who he saw as trampling on his artistic license. For instance, he wanted to give the house unusually low ceilings, 7’6″ instead of the required 8′. Denied, he recorded his losing battles in a series of four bas-reliefs in the front hall; one shows an architect being stomped by an authoritarian foot while another depicts him strangled in red tape.

Although the house had been planned as a starter home, the Towsleys lived there all of their lives. They just kept asking Dow to design additions, which he did in 1934, 1938, and again in 1960. Dow put his latest ideas into each revision such as a landscaped backyard viewed through a big dining room window and so many built-ins that there was little need for furniture: he provided a built-in safe, walk-in refrigerator, clothes drawers that opened on both the bedroom and dressing room sides, and even metal drawers especially designed to store Margaret Towsley’s extensive collection of linen tablecloths. The original color scheme was vividly patriotic in the main living areas: cherry-red rug and turquoise walls.

In 1933, Alden and Vada Dow spent six months at Taliesin, Frank Lloyd Wright’s studio-home complex in western Wisconsin. While Alden studied architecture, Vada completed her own fellowship in painting, weaving, and pottery.

Dow and Wright maintained a friendship for years after the Dows’ time at Taliesin. The two architects visited each other in their homes and Dow even named one of his daughters “Lloyd.” They had a serious falling out, however, in 1949, when Wright lost a commission to design the Phoenix Civic Center because his fee was too high–and Dow agreed to take the job in his place. According to Craig McDonald, director of the Alden Dow Home and Studio in Midland, it was Vada Dow and Olgivanna Wright who finally persuaded their husbands to make peace.

After Taliesin, Dow set up his own firm in Midland. Despite the Depression, Dow Chemical was booming, and he designed homes for an ever-increasing circle of clients. As his reputation grew, he received commissions from as far away as North Carolina (a residence for the president of Duke University) and Texas (an entire company town, Lake Jackson, for Dow Chemical during World War II). But Midland always remained his base: of the 138 buildings he designed in his career, 104 are in his hometown.

Ann Arbor is second only to Midland, with eighteen Dow buildings. Surprisingly, very few are private homes; he built only two more residences here, both for doctors who knew Harry Towsley: the Sibley Hoobler house (228 Belmont Road) in 1949, and the Joe Morris house (7 Regent Drive) in 1962. Hoobler has since died, but Joe and Julia Morris still live in their Dow house and vividly remember the design process.

In the early 1960s, Joe Morris asked Harry Towsley whether he thought Dow would design him a house. Towsley suggested that he write and ask, and Dow responded by inviting Morris to Midland for lunch. During lunch, Morris recalls, the architect “talked about sailboats, about housing–he had an idea about housing for Third World countries by making plastic modular units and dropping them in by helicopter. When we returned, I told his secretary we hadn’t talked about my house. She said, ‘Wonderful. He needs to get his mind off his work.’ ”

The Morrises waited two years before Dow had time to work on their house. When they finally sat down to review the plans, they found that Dow had definite ideas about what he wanted. For instance, Joe recalls, Dow’s original plan did not include room to eat in the kitchen–“He said we would never eat in the kitchen.”

“We insisted we would,” Morris continues. “So he relented and designed a [built-in] kitchen table.” The furniture that Dow didn’t build in, he selected, including daybeds, dining room table and chairs, and the chairs and sofa in the living room. All of the built-ins and carefully coordinated furniture result in a very clean look. Morris calls it “magnificent simplicity.”

Joe Morris was one of many clients invited to visit Dow’s combined home and studio in Midland. A beautiful and unusual building, it was a good advertisement for his artistry.

Like the Towsley house, Dow’s evolved in a series of additions. It began in 1933 as a long train car–like studio. In 1935, he added its most striking feature, a room half-submerged in a pond. Officially called the “floating conference room,” but known informally as the “submarine room,” its ingenious use of water invites comparisons to Wright’s more famous Falling Water.

In Midland, Dow was able to build the low ceilings he was denied in Ann Arbor. “I got a kick out of his studio,” recalls Fred Mayer, U-M’s director of university planning. “He was about 5’6″, so the studio was designed for him. I’m 5’8″, so it was okay with me.”

The low ceilings and small proportions in Dow’s house reminded Morris of “Beatrice Potter homes in Peter Rabbit. There was the same childhood comfort in his home.” Bill Reish, who visited Midland in the seventies to discuss an addition to Greenhills School, recalls the “sunken room at duck-eye level, with ducks floating by.” Former library director Gene Wilson missed that view–“The pond was leaking the day I was there, so he had it drained.”

People remember Dow’s appearance as slightly eccentric. “He was wearing different-colored shoes, I think yellow,” Wilson recalls. Adds Rumelhart, “He wore his hair longer than the conventional doctors I was used to.”

Craig McDonald, who was Vada’s assistant in the last years of her life, recalls Alden as “quiet and understated. He was somewhat shy, but expressed himself through design.” The late Guy Larcom, who oversaw construction of Ann Arbor’s city hall, remembered him as “a small man, undistinguished–but impressive when he talked about architecture.”

“He could be very intense if he got excited about something,” Rumelhart says. “He could pick a flower and be overwhelmed. He had a creative intensity.

“I loved Alden,” Rumelhart continues. “He said it was okay to be a singer. The medical world was terrified of the arts, but he told my parents, ‘She’s talented. She should be doing what she is doing.’ ”

Dow’s peak period in Ann Arbor came during the 1950s and 1960s when he built six university and three civic buildings. The U-M’s Margaret Bell Pool (1952) was his first college commission; it opened doors, and he eventually worked on nine other campuses in Michigan.

Before it was built, the U-M had two pools reserved primarily for men, while women had only the “Barbour bathtub” in the basement of Barbour gym. Margaret Bell, head of women’s physical education, had long wanted to redress this injustice. According to Sheryl Szady, who has researched the history of U-M women’s athletics, “She said, ‘Before I leave, I’m getting a pool.’ ” Bell organized bridge parties, sold tiles, and organized benefit parties to raise the necessary funds. Margaret Towsley, a friend of P.E. professor Marie Hartwig and a generous patron of progressive causes, probably contributed to the project.

The new pool was state of the art. Designed for synchronized swimming and for Michifish shows (elaborate performances with costumes, lighting, and staging), it had an air flow system that sent cool air over the spectators in the bleachers and warm air over the pool. Underwater speakers allowed the synchronized swimmers to hear the music.

According to Szady, the day before the pool opened, Bell, Hartwig, and another woman “hopped in and played around.” At first, men were allowed to swim at the pool only on Friday nights. The pool became coed in 1976 when the building was enlarged to become the Central Campus Recreational Building. Last year the kinesiology department put on another addition, but Dow’s original building is still discernible, especially the second-story planters, the only ones in Ann Arbor that are still maintained.

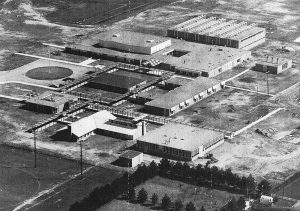

In 1964, Dow designing two large buildings just a half a block apart on Thompson Street: ISR, the first new building in the country dedicated solely to social research, and the administration building, later named in honor of Robben Fleming, the university’s tenth president.

The two buildings have striking exteriors, but both have been criticized as being designed from the outside in, sacrificing interior utility to achieve an exterior effect. For instance, as originally designed, the massive white aggregate panels that face ISR would have left the offices behind them with no exterior windows. According to retired psychology professor Bob Kahn, one of ISR’s founders, Dow had to be persuaded to move the panels out slightly so that small slit windows could be added.

Dow planned ISR’s interior in detail. The space was divided into modules, each with a large open area facing a window wall, with two offices on either side of the open area and two slightly bigger offices in the corners. “The offices would be almost all one of two sizes to minimize status,” recalls Kahn. Dow was proud of the egalitarian effect, noting in his 1970 book, Reflections, “All occupants have a similar relationship, through glassed area, with the outside.”

But research projects did not always divide neatly into the modules Dow prescribed. And despite his egalitarian goals in designing the faculty offices, the ISR layout also perpetuated what, in hindsight, looks like a far greater inequity: while the researchers had private offices, the female support staff was assigned to desks that sat in the middle of the central area, without a shred of private space. Room dividers were eventually added–but these in turn blocked out light to the side offices.

Maintenance on the windows also presented a problem. They were locked with special keys and pivoted open to wash. People would open the windows to let in air, then not secure them because they didn’t have the key. Once, “a person on the fifth floor was leaning against the window when it pivoted,” recalls retired ISR administrator Jim Wessell. “He almost fell out. Luckily he was caught by someone nearby.”

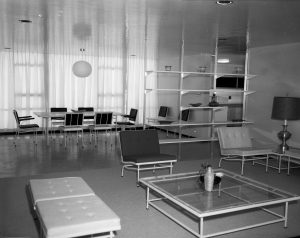

The windows on the Fleming Administration Building opened the same way but were arranged very differently: in geometric patterns reminiscent of a Mondrian painting. While intriguing from the outside, the design created some very curious interior spaces, with long, thin windows in unpredictable locations.

Dow’s most unusual campus building, the Fleming Building, is also the most controversial. Ed Surovell calls it “a cube in space” and says of the entrance, “you have to hunt for it like a medieval castle.” People who work in the building complain of the “mazelike” layout.

The Regents’ Room on the first floor is designed with an arched ceiling, which, according to Craig McDonald, was used “to give a feeling of being in a larger space.” Two similar arches take up the rest of the first floor: the middle arch is a corridor connecting the east and west entrances, and the other serves as offices. The cavernous look has caused people to compare the space to a beer vault or a wine cellar, and audiences at regents’ meetings often decry the absence of windows and call it “the cave.”

Rumelhart defends the design, saying, “Alden took the assignment and created a painting. He was a great fan of Mondrian and he fulfilled that feeling.” Also siding with Rumelhart is architect Denise Scott Brown. Asked about the Fleming Building, she calls it “honorable architecture” and says it is “nicely proportioned.” “Taste cycles,” adds Brown’s husband, Robert Venturi. “There was a time when Victorian architecture was thought ugly and torn down. We have to be tolerant of the immediate past.”

Changing taste is one problem with the building, but of the more utilitarian problems, many are not Dow’s fault but are the result of growth. “It was never intended to have as many people as it does now. When there was a big lobby on every floor, it was more aesthetically pleasing,” says Dick Kennedy, retired vice-president for government relations.

“You’d get off the elevator and see a bank of windows onto the plaza,” recalls Kay Beattie, who worked in the building in its early days. “You had the feeling no one worked there.” Beattie also remembers that, in vintage Dow fashion, each floor had its own vivid color theme–longtime employees describe them with names like “Howard Johnson orange” and “football field green.”

As controversial as the Fleming Building is, it could have been even more eye-popping. According to Fred Mayer, university architect Howard Hacken vetoed Dow’s original plans to finish the exterior in white stucco with blue windows and gold trim. “Very rah-rah,” Mayer laughs.

Dow left a strong mark on the U-M campus, but it was nothing compared to his impact across Division Street. In the library and city hall, he defined the two most important buildings in Ann Arbor’s public life.

The library was built first, in 1956. “After the war there was no established library architecture,” recalls Gene Wilson, then a library staff member, later director. “Dow had built the Midland library, and we thought it was grand.”

His Ann Arbor design had all of the Dow hallmarks. Even today, after two additions, one can still recognize his hand in the elevated planter faced with turquoise enamel paneling and the lovely little garden on the south side.

“I always liked it,” Wilson says of the library. “It was state of the art for its time.” But, he admits, there were problems. “Dow was more concerned with visual impact–he wanted it to be noticed, he didn’t let function get in the way. There was a circulation desk but no reference desk, and there was no clear delineation between public and private areas. We had to scramble around to make [the layout] work.”

Like many other clients, the library also found that Dow’s elevated gardens were difficult to maintain. Wilson doesn’t recall exactly when the library stopped tending the second-story planters, but says, “it would have been very early. There never was a way to get to them except by a long ladder put up by the sidewalk–any maintenance was done by the janitor climbing the ladder. One day the ladder slipped and the janitor fell and broke his leg. After that we lost enthusiasm.”

Dow’s other great downtown project, the Ann Arbor city hall, has been a conversation piece ever since it opened in 1961; in addition to a chest of drawers, it’s been compared to “an inverted wedding cake” and “an upside-down carport.” It’s also been called “a poor man’s Guggenheim,” an allusion to Frank Lloyd Wright’s famous upward-spiraling museum in New York City.

The building is an inverted stepped pyramid, with the floors growing wider as they go up. The second floor is a large promenade that Dow thought might be used for public meetings or for city council members to step outside to caucus. (Rumelhart has always thought it would be a good place to perform plays.)

Inside, Dow put elevators, stairs, conference rooms, and department head’s offices near the building’s core. The space around the periphery of the building was kept open. “The idea was that there were to be no prestige offices, no best windows,” recalled Guy Larcom in an interview before his death last winter. “It was all open to public view.”

Kathy Frisinger, then the city’s assistant director of central services, oversaw the move into the new building. She remembers that although employees were glad to be together after being scattered at seven different locations, many didn’t like the open floor plan. “You could see from one end to the other,” she explains. “If you talked to someone, everyone could see you talking, see which office you went into.”

The promenade never got much use, and there were serious problems with roof leaks. Switchboard operator Mary Schlecht recalls that when it rained, the police department downstairs had buckets all over the place. The planters Dow specified on the second and third floors also leaked. “The plants grew well on the north side, but it got too hot on the south and you had to water almost every day,” a former employee recalls. City hall’s maintenance people, like their counterparts at the library, eventually gave up on the planters; they’re now filled with rocks.

Dow ordered the building’s furnishings with his characteristic eye for vivid color. “I’ll never forget that day when seven Steelcase trucks came. Big semi trucks drove up with turquoise and orange furniture,” laughs Frisinger, who supervised the unloading. “I saw mine were to be orange and I said, ‘I don’t think so,’ and did a quick switch.” Nonetheless, she says, “I basically enjoyed the building. I liked the big offices, the open spacious feel in the building. Dow was ahead of his time.”

As city hall has become more crowded, its once open spaces have given way to a warren of cubbyholes. Furniture and curtains have been placed in front of most of the big windows in the inner offices to give more privacy. The top floor, recently remodeled after the district court moved to the county courthouse, today comes the closest to the spacious feeling Dow originally intended.

Dow worked up to his death in 1983, but the debate continues on his rightful place in architectural history. The question of whether or not his buildings look good comes down to personal taste, and there can be no global or permanent answer. Setting that aside, a study of his Ann Arbor work shows that while many have serious practical problems, there were always reasons for what Dow did.

Near the top of the list of problems would have to be his flat roofs, a distinction he shared with his mentor, Frank Lloyd Wright. “Talk with any person about an Alden Dow building and they will sing its praises and then remember the trouble they had with the roof,” says Greenhills’ Bill Reish. Dow’s elevated planters were another recurring source of trouble. The only one still in use in Ann Arbor, at the U-M’s kinesiology building, supports a few scraggly plants. Ann Arbor has apparently tended its Dow buildings less carefully than his hometown. Craig McDonald reports that numerous examples of Dow’s elevated plantings are still flourishing in Midland.

Lighting could be listed among Dow’s greatest failures but also among his greatest successes. It was obviously a lifelong obsession and when it worked, it worked gloriously, as in the big windows that both let in light and created splendid views in his private homes. When his plans went astray, however, people worked in dark caverns such as those in the Fleming Building and ISR.

It could be argued that these failures were not so much design errors as a misreading of human nature, especially the need for privacy. “Human nature will confound you if you fight it too much, even with a good idea,” comments Fred Mayer.

Dow seems to have been the most successful in his smaller projects, particularly the private residences where he could think out the use of every inch of space. In the larger buildings, he was most successful in the ones built for a specific use, particularly those associated with family members such as Greenhills or the medical education building.

Some of Dow’s critics complain that he received the Ann Arbor jobs only because of his connections with the Towsley family. Certainly some of his work came directly through his sister and her husband, or as a result of friendships or community contacts made through them. Fred Mayer defends Dow on this score. “Having connections will give you a chance,” he says, “but if you don’t do something good, it won’t save you.”

Most of the serious criticism of Dow is aimed at his multistory buildings. Architects don’t like to speak ill of other architects, even dead ones, but off the record, several express doubts about Dow’s “bulky, boring” multistory designs.

“Nothing is related to human scale in ISR. It’s just a big white space,” says one architect–who goes on to describe the Fleming building as “weird.” But Mayer again comes to Dow’s defense. “He was a talented architect,” he says. “I don’t know if he will make it in the ranks of the great, but talent and creativity are evident in his best buildings.”

Dan Jacobs, who’s designed several additions to Greenhills, agrees. “I’m a great admirer of Dow. I admire the simplicity of his structural system.”

Despite the complaints, it should be noted that all of his Ann Arbor designs, except for one razed gas station, are still being used for their original purpose. Even the Fleming building, threatened during Bollinger’s term with a changed use, is still the administration building. Asked about Bollinger’s dislike of her uncle’s building, Judy Dow Rumelhart lets out a good-humored laugh–but then admits that she has chided Bollinger for his criticism of the building. “He can move out, but I hope he uses it for something else, maybe English classes,” she says. “Let it be used by someone to enjoy.”

An Alden Dow Chronology:

Between 1932 and 1970, Dow designed eighteen Ann Arbor buildings. Details are given only for buildings not described in the main story.

1932: Towsley home, 1000 Berkshire.

1949: Hoobler home, 228 Belmont.

1952: Margaret Bell Pool (U-M).

1956: Ann Arbor District Library, 343 S. Fifth Ave.

1958: Ann Arbor Community Center, 625 N. Main. Dow designed the building at the request of his sister, Margaret Towsley. Towsley not only contributed most of the cost, she also paid for many of the buildings furnishings–even dishes and towels.

1959–1965: Matthaei Botanical Gardens, (U-M). The gardens’ offices and conservatory are instantly recognizable as Dow’s work thanks to the turquoise-faced second-story planters (long since abandoned). Herb Wagner, professor emeritus of botany, remembers fighting to include a lobby and meeting room in the plans; more than thirty years later, Wagner says, it remains “one of the best university botanical gardens in the nation.” Dow also designed the garden superintendent’s house.

1960: Leonard gas station, 2020 W. Stadium. Possibly conceived as a prototype for Michigan-based Leonard, this simple, well-landscaped gas station was Dow’s first commercial work in Ann Arbor. It is the only Ann Arbor Dow building no longer standing.

1961: Guy J. Larcom Jr. Municipal Building, 100 N. Fifth Ave.

1962: Morris home, 7 Regent.

1962: Conductron headquarters, 3475 Plymouth. Keeve “Kip” Seigel, founder of the high-flying Conduction conglomerate, was a friend of the Towsleys. The low-slung brick building is currently the headquarters of NSF International.

1963: University Microfilms, 300 N. Zeeb. Dow met University Microfilms founder Gene Power, a U-M regent, through the Towsleys. To recycle water used in processing microfilm, he included a moat on the south side of the building, creating what he called “a reflecting pool for office and cafeteria.”

1964: Institute for Social Research (U-M).

1964: Fleming Administration Building (U-M).

1964: Michigan District Headquarters, Lutheran Church Missouri Synod, 3773 Geddes. Dow built some lovely churches in Midland, but this is his only church-related structure in Ann Arbor. Its four wings are grouped in the shape of a Greek cross; the teepee-like dome on top symbolizes the church’s early Indian missions.

1966: Towsley Center for Continuing Medical Education (U-M). Dow’s last major job for the university was arguably his most successful. One of Harry Towsley’s specialties was continuing education, and the brothers-in-law collaborated closely on a simple, straightforward building marked with Dow trademarks such as long corridors filled with windows and plants. “It’s state of the art, designed for traffic flow, with an auditorium and four break-out rooms, a huge lobby,” facilities coordinator Robert Witte says. “If I was ever asked to design a medical education building, I would design it off the Towsley Center.”

1967: Greenhills School, 850 Greenhills. Judy Dow Rumelhart was a member of the original planning committee for this private north-side school, and Margaret Towsley was on the first board. Dow laid out the building as a series of clusters, each with classrooms around the edge and a court in the middle. In the middle of each court is a common space called a “forum”; in the corners are areas for quiet activity, called “alcoves.”

Starting in 1968 with grades 9–12, Greenhills gradually expanded to accommodate grades 6–12. By opening alcoves and linking them to new clusters, Dow designed additions that felt as if they were part of the original. Over the years, the brown walls and curiously colored carpets Dow specified have been toned down, and doors have been added to control noise. Still, Bill Reish says, “It works wonderfully as a school.”

1970: 2929 Plymouth. After Gene Power stepped down from University Microfilms, he commissioned Dow to build this small office building just east of Huron Parkway. “I was glad I selected Alden, because my site presented a difficult design problem,” Power recalled in his autobiography, Edition of One. “The zoning regulations stated that floor space could not exceed 40 percent of the land area. There had to be one automobile parking space available for every 110 square feet of floor space, and the structure could be no more than three stories high. Dow met these requirements by raising the building on columns, with only a small entrance lobby and elevator area extending down to the ground-floor level. Most of the area on that level formed a parking lot beneath the rest of the building.”

Power’s son, U-M regent Phil Power, recalls the office as “a lovely place to work. It had a beautiful view of North Campus. It had a fireplace, shelves with Eskimo art, orchids, a nice sitting area, and was lined with bookshelves.” The building—which always reminded Rumelhart of “a giant toadstool”—is now rented to a number of small tenants.

[Photo caption from book]: Dow was proud of his egalitarian design for the faculty offices at the ISR. But he also perpetuated what, in hindsight, looks like a far greater inequity: while the researchers had private offices, the female support staff was assigned to desks in the middle of the central area, without a shred of private space.

Published on a2modern with permission of the author.