Metcalf Modern

Author: Grace Shackman

In the 1960s, U-M Profs sometimes waited years for architect Bob Metcalf to design their homes. Now his mid-century designs are back in fashion.

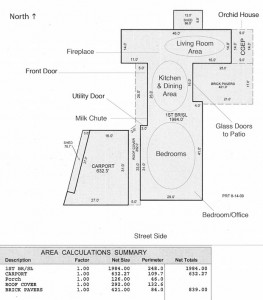

Bob Metcalf, at age eighty-seven, is adding a two-car garage to his house on 1052 Arlington. He already has a one-car garage and isn’t currently driving, but he’s building it now because he can’t bear the thought of a later owner doing it badly. “I figure they would wreck the house by putting the garage right out in front,” he explains.

The house is very special to Metcalf‹he and his late wife, Bettie, built it themselves in 1953. Using it as a showcase, he went on to design sixty-eight houses in Ann Arbor. All are in the style now known as “mid-century modem,” and, after a period of being ignored, are treasured by a growing community of admirers.

Metcalf’s new garage is a little south of the existing home so it doesn’t interfere with the entrance. The original one-car garage on the other side of the house was the first thing that the Metcalfs built in order to have a place to store their tools during construction.

Bettie Metcalf found a large lot in the then-unsettled Ann Arbor Hills, just outside the eastern city limits. (The subdivision was laid out in 1927, but very few houses were built during the Depression and World War II.) Bob Metcalf spent a year drawing up the house plans. They started work in April 1952 and moved in just over a year later.

At the time, the U-M architecture grad was working as a draftsman for George Brigham, one of the first architects in the area to odern-style houses. Metcalf would work for Brigham from 6 a.m. until 2 p.m. and then head over to the construction site. Bettie would join him at 4 p.m. after getting off from her nursing job at the University of Michigan Health Service. She would bring the supper that she had made the night before, which they would eat sitting in the car.

They did all the labor themselves except the work required by law to be done by specialists, such as electricity and plumbing. Design decisions were based on aesthetics, their skills, and what they could.afford. Metcalf didn’t know how to plaster, so he made the interior walls out of cedar (relatively cheap then). He got the idea of putting in a brick floor from a friend who had done that for a project with Alden Dow in Midland‹according to Metcalf’s construction journal, he paid five cents a brick.

Homes that George Brigham designed were filled with light coming in from large south-facing windows. Metcalf made his windows even larger and angled them more to the southeast‹an orientation, he says, that lets in “less sun in summer but [more] heat gain in winter.” Like most mid-century modem designs, the house has a flat roof. Rainwater drained into the backyard through an interior pipe, in effect creating a rain garden long before they be- came popular.

The couple’s work paid off. Before the house was even finished, Metcalf had received five commissions, all from U-M faculty members‹vindicating his belief that Ann Arbor would appreciate the type of house he wanted to build.

Metcalf was born in 1923 in the small town of Nashville, Ohio. His dad. dis- appeared when he was young, and his mother moved to nearby Canton, where she worked as a maid and later remarried. When Metcalf was six or seven, a visiting uncle saw the way he was playing with objects on the floor and told him “you ought to be an architect.”

He enrolled in the U-M architecture school in 1941 but was drafted to serve in WWII. He and Bettie had dated after high school, and just before Memorial Day in 1943, he called and asked her to come down to Louisiana, where he was stationed, for the holiday. When she asked why, he replied, “Because we’re going to get married.” And so a three-day engagement led to a sixty-five year marriage. Metcalf returned to the U-M after the war, and graduated with a bachelor’s degree in 1950. As graduation grew closer, Metcalf asked Brigham, a professor he thought highly of, if he could work for him. He liked the way Brigham took into account “the impact of the environment on a building,” he recalls, and was also impressed that Brigham was the only member of the architecture faculty who invited students to his house. Brigham hired him as a draftsman at $1 an hour.

After four years with Brigham, Metcalf began his own business. His first commission was from physics professor Richard Crane and his wife, Florence, who wanted a house in which they could be separated from the noise and clutter of their teenage children. Metcalf obliged by designing their home at 830 Avon with an entrance on the side that led from the left into the living room and master bedroom and from the right into a kitchen and family room, with the children’s rooms on the other end.

In addition to his architectural practice, Metcalf taught at the U-M. Within two years, he had so many jobs he asked two young U-M colleagues, Tivador Balogh and William Werner, to join him. “We worked in his own house, but it wasn’t satisfactory and after a month we moved into his one-car garage,” recalls Wemer. With only a space heater for warmth, he says, “it was so bad, it was wonderful.”

Metcalf eventually moved into an office at 444 South Main, renting the first floor from builder Zeke Jabbour. Balogh did freehand drawings to give clients an idea of what their house would look like, while Wemer did many of the calculations and detailed working drawings. When Balogh left in 1960, he was replaced by Gordie Rogers, who had studied under him. Bettie Metcalf didn’t work in the office but was always an important part of the operation, keeping the books, typing letters, and ordering furniture.

Some clients knew just what they wanted. The woman for whom he designed 2576 Devonshire, Metcalf recalls, wanted lots of white walls to display her art collection (he remembers her bragging that she had an original Kandinsky hanging above her washing machine‹and that she’d paid $25 for it in Paris). A home at 1329 Glendaloch has a center courtyard, because its first owner had seen that in South America. But Metcalf says most clients weren’t so definite, so he would interview them for several hours to get an idea of their needs: “I’d ask them how they use a house‹if they had meetings where people talked together, if they played cards, what activities they did when they had company, if they read.”

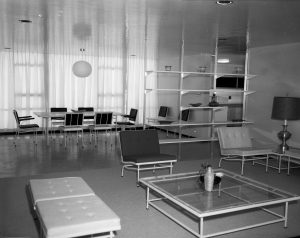

Metcalf designed houses starting from the inside. He’d block out how the rooms should be arranged, including where furniture should go. He’d figure out the best view from inside as well as how to bring in the most natural light. He often used grilles he designed to serve as room dividers. The exteriors were usually a series of boxes arranged in interesting ways, sometimes on different levels so they snuggled into the landscape. John Holland, one of the few original owners who still lives in his Metcalf house, recalls how before starting work in 1964, the architect “walked all around [the site] and thought [about] what fit naturally.”

The Holland house at 3800 W. Huron River Drive sits high on a knoll with a view of the river below. Because the knoll was flat, Metcalf stepped a bedroom up half a story to give the roof a more interesting look. The house includes many of his signature features, including a big window angled southeast, lots of built-ins including a buffet, desk, and bookcases, and careful use of wood throughout cedar outside and vertical grain fir inside. “There’s not a day I haven’t been happy to be in this house,” says Holland.

By then, the firm was so busy that another client, aerospace engineering prof Elmer Gilbert, waited several years for the architect to be available. Gilbert was single at the time; he later married Lois Verbrugge, and they still live in the house at 2659 Heather Way.

The home is more vertical than many of Metcalf’s designs: taking advantage of the sloping site, it is two stories in front, three in back. Because the street side faces south, Metcalf placed his requisite big windows on the north side, but did so in a spectacular way: they’re three stories high, and the top floor is a mezzanine that stops before reaching the windows, so light spills down to the first floor.

The siding is cedar, and the inside trim mahogany. The house is still filled with original top-line mid-century modem furniture‹Saarinen, Eames, Bertoia–which Bettie Metcalf ordered so Gilbert could get the 40 percent architect’s discount.

Metcalf varied materials and size depending on the means of his clients but never abandoned his basic principles. For instance, in 1957 he designed an inexpensive house at 2466 Newport for anthropologist Marshall Sahlins, then a low-paid assistant professor with two kids. The siding is cement block and plywood, and the inside is finished in inexpensive materials such as tile and Masonite, but Metcalf still did amazing things with siting and light. The house sits on the western edge of the property with big windows facing east giving a view of the rest of the wooded lot.

Present owners Judy and Bob Marans, who bought the house in 1974 when it was pretty run-down, have made many improvements over the years, including enclosing the foyer, adding a garage, and modernizing the kitchen and bathrooms, but they still have kept the basic structure, which they love. Judy Marans remembers thinking when they moved into the house, “When will I get used to the beauty of this? The answer is never.”

Metcalf began teaching at Michigan as a visiting lecturer shortly after he graduated. In 1958 he became an assistant professor, promoted to associate in 1963. When he was hired, he recalls, he proposed that he teach “a construction class that every student had to take. It sounds logical, but no one was doing it.”

Architects Norm and llene Tyier, who took Metcalf’s classes in the 1960s, recall that their most important assignment was to find an active construction site and visit it every day, jotting down observations in a journal. llene watched the building of the U-M’s Oxford Houses, while Norm followed an apartment being built near the Blue Front on South State. “It was one of the best things I did as a student,” he re- calls. “There was no greater respecter of Mies van der Rone’s statement that ‘God is in the details’ than Metcalf.”

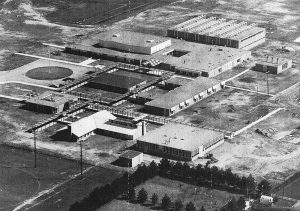

In 1968 Metcalf was made a full professor and chair of the architecture department, and in 1974 he became the first dean of the newly named College of Architecture and Urban Planning. The promotions greatly reduced the time he could devote to his private architecture practice.

From 1953 to 1968, Metcalf worked on 100 jobs‹not only houses, but offices, sororities, churches (his Church of the Good Shepherd won several awards), and park shelters. Over the next twenty-three years, when he was absorbed in the work of running the architecture school, he did only twenty private commissions. “He realized he couldn’t do both at once,” explains Werner.

When Metcalf retired in 1991, he returned to his architectural practice. Werner rejoined him after he retired seven years later “It took the sting out of retirement,” he says. But while they were busy in academia, the popularity of the mid-century modem style had waned.

The simple, uncluttered look that seemed so revolutionary to their parents struck many Baby Boomers as cold and sterile. Often built on modest budgets and with a minimalist aesthetic, many homes seemed small by contemporary standards. And there was a feeling that modern houses, with their large windows, flat roofs, and easy flow from indoors to outdoors, fit better in California’s climate, where they originated, than in the Midwest.

Meanwhile, postmodernism, with its return to ornamentation, and historic preservation, which celebrated premodern styles, both grew in popularity. Though Metcalf has done thirty commissions since he retired, only three of them have been for new homes.

In the past twenty years, most of his work has involved modifying his own past designs. Holland contracted with him to build a bigger living room and later to add a bedroom and bathroom in the space between the garage and house. When Gilbert married Verbrugge, he asked Metcalf to figure out how to add a study for her on the ground floor as well as making other improvements.

Since the 1950s, home buyers have grown accustomed to more space, more bathrooms, and bigger kitchens. Over the years, many owners have remodeled their Metcalf houses. His admirers often show up at open houses when they go on the market, as does Metcalf himself. Sometimes he finds that there are no changes, but in most cases they have been modified and are often, in his words, “worse as far as I’m concerned.” When people ask, he is always willing to show them the original plans and help to do new additions or undo old ones.

Nancy and David Deromedi asked him to help with their house at 819 Avon, a 1950 Brigham design that Metcalf had worked on. The house, built for famous anthropologist Leslie White and his wife, Mary, had been modified by later owners with a snout-nosed garage extension that stuck out toward the street with a porch sitting awkwardly on top of it. When David drove up to attend an open house, he didn’t even want to stop, but Nancy convinced him it was worth looking inside.

They bought the house in 2005 and asked Metcalf to figure out how to undo the damage. He solved the garage problem by simply returning it to the original dimension. A second problem, dating to the original design, was a long outdoor entrance staircase, especially treacherous in the winter. Metcalf moved the inside entry outward, creating a well-lit foyer that covered about half the stairs.

Beyond keeping the respect of his clients, Metcalf also became friends with many of them. Holland often stopped in at his office to say hello, while Gilbert and Verbrugge periodically invite him to dinner. At Bettie’s memorial service in 2008, the room was filled with people who felt a connection with Metcalf because they lived in one of his houses.

And he’s lived long enough to see his designs appreciated by a new generation. Lois Kane, who lived in a Brigham house in Barton Hills, sees young people returning to an appreciation of the environmental and social pluses of living simply, of the “less is more” philosophy. When she and her husband, Gordie, sold their house four years ago, she says, they realized “it would appeal to people who read Dwell [a magazine celebrating modern style and simple living], not Better Homes and Gardens.”

When Monica Ponce de Leon was appointed dean of the school of Architecture and Urban Planning, she and her husband, Greg Saldana, bought a Metcalf house at 715 Spring Valley in Barton Hills. Metcalf designed it for Millard Pryor in 1958. Ponce de Leon, who had been on the faculty of Harvard, knew of Metcalf’s work and specifically hunted for one of his houses when moving to Ann Arbor.

When Metcalf heard of the purchase, he showed up at the couple’s hotel room with his original drawings. Saldana, an architect whose specialty is architectural conservation, used the drawings to restore the house.

Saldana says they constantly get compliments on their Metcalf. “Very recently we hosted a highly accomplished artist who did not know of Bob Metcalf,” Saldana emails, “and upon entering our home said, ‘what a beautiful home–who designed it?'”

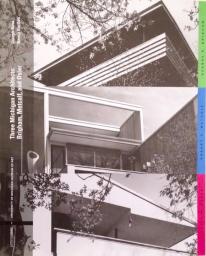

Three Michigan Architects: Brigham, Metcalf, and Osler

Three Michigan Architects: Brigham, Metcalf, and Osler